While science fiction worlds are (somewhat) constrained by the laws of physics1 the same is not necessarily true of fantasy worlds. Despite this, many fantasy worlds are slight variations on Earth as we know it. Sometimes the continents are different, but generally speaking, the working model is “standard Earth plus magic.” Only generally speaking, however—there are exceptions. Here are five.

Under the Pendulum Sun by Jeannette Ng (2017)

The fairy lands of Ng’s novel Under the Pendulum Sun are as unlike Earth as the Fair Folk are unlike humans. Above the flat plain occupied by this world’s inhabitants, a bright sun oscillates on the end of a long string—the pendulum sun of the book’s title. Very conveniently for my purposes, Ng not only acquired the services of a physicist to determine what such a world would be like, she documented the resulting process2 in her 2018 essay The Science of the Pendulum Sun. Rather than settle for the first, simple model (sun on string), Ng tweaked her worldbuilding to produce a gothic setting that is perfect as a backdrop for her “Jane Eyre on LSD” fantasy novel.

Glorantha by Greg Stafford (1966*)

Although Stafford began work on his Bronze Age fantasy setting of Glorantha in the 1960s, it was not generally available to the public until the 1970s, when game company Chaosium incorporated the setting into board games like White Bear and Red Moon and Nomad Gods, and most significantly (at least from my personal perspective), the roleplaying game RuneQuest.

On a small scale, Glorantha looks Earth-like, featuring two large continents separated by a vast sea. Pull back for greater perspective, and this familiar arrangement is revealed as the top of a cube floating in a sea of chaos, surrounded by a great sphere beyond which sensible mortals do not explore. This is a magic-imbued world operating according to rules entirely unlike the rules of our world3 and the shape of the world reflects that.

Tales From the Flat Earth by Tanith Lee (1978–1987)

This collection comprises Night’s Master (1978), Death’s Master (1979), Delusion’s Master (1981), Delirium’s Mistress (1986), Night’s Sorceries (1987), and various short works.

Tanith Lee’s Flat Earth is a world where the haughty gods consign mortals—whom gods see as an embarrassing mistake—to the care of demons and other deliciously malevolent beings. It is also, as many of you may have guessed by this point, as flat as a tabletop. It is interesting that this flatness is a temporary condition (as is signaled by the phrase “for in those days the Earth was flat”). This Earth must be immune to the tendency of gravity to pull worlds into spheres.

The world is perverse in other ways: its lascivious inhabitants disregard convention; amorous limitations imposed by basic anatomy are ignored (humans boinking flowers, kobolds boinking spiders, etc.).

Like Ng, Lee made notes on her world. However, the only fragment of these notes of which I am aware is a brief except and a drawing in a recent reprint of Night’s Master.

The Discworld by Terry Pratchett (1983–2015)

Comprised of a sufficiently large number of books that if all were listed, there would be no room for an essay4, the Discworld is not merely the disc implied by the name but a disc balanced on the backs of four immense elephants: Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon, and Jerakeen. These elephants stand on the back of an even more enormous turtle, A’Tuin. This implausible arrangement is an early hint that on the Discworld, narrative forces are far more powerful than mere physical law. Pratchett’s stories require a setting that is simultaneously awe-inspiring and absurd: the Discworld is that setting.

Pratchett having in his time been a publishing juggernaut, his world is documented in any number of places online and elsewhere. Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen 1999’s The Science of Discworld is a good start.

Missile Gap by Charles Stross (2006)

Technically, this tale of Cold War rivalry complicated by alien intervention is science fiction. However, since it is set on an Alderson disc—a massive platter of solid material millions of kilometres across—and since no known material could prevent such a construct from being immediately reshaped by gravity into a more conventional arrangement, it feels sufficiently fantasy-adjacent to mention here. In this particular case, unknown entities have populated a flat projection of the Earth’s surface with Cold War-era humans. The necessary differences between a flat map and a sphere dramatically alter the balance of power between Americans and Soviets. If only West vs East were the most pressing concern confronting humans…

Stross credits the story seed to a post made on the now effectively defunct USENET newsgroup soc.history.what-if by a Canadian whose name eludes me. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that the Canadian was himself inspired by Fred Hoyle’s October the First is Too Late and Larry Niven’s “Bigger Than Worlds,” assuming for the moment that Canadians had access to printed material as early as the ’00s.

***

These are just a few of the possibilities that came to mind. No doubt there are many others (if only because I know there was a Dave Duncan novel that I could have mentioned but did not). Many of you may have your own favourites. Comments are, as ever, below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and the Aurora finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is eligible to be nominated again this year, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]SF is approximately scientific. It has to look scientific, even while it assumes current impossibilities like anti-grav, wormholes, FTL travel, ubiquitous fusion, etc. Sometimes the handwavium fails.

[2]I encountered the essay before I encountered Ng’s novel. In fact, the essay is what made me seek out “Under the Pendulum Sun,” and now, years later, is what made me think about world shapes in fantasy. Thus, contrary to my usual habit of sorting by publication date, Ng gets the lead position in this essay.

[3]Once again, small-scale events produce the same outcomes as on Earth, which is to say mortals are very mortal and a sword blow to the head will ruin your whole day. Happily, magic can often reattach severed body parts.

[4]A simple list would be long enough to break Tordotcom’s footnotes, which is why there is no list here, either.

John Crowley’s first novel, The Deep, is set on a very strange world — a plate perched on the top of a pillar in space.

It’s ambiguous whether it’s SF or Fantasy. It’s an exceptional novel, however.

And thanks for the mention of “Missile Gap” — that one really wowed me!

The Shattered World and its sequel The Burning Realm, by Michael Reaves, take place on a version of Earth that has been, well, shattered — broken into thousands of shards, ranging from a large rock to the size of an archipelago of islands. Magic keeps the whole mess in a breathable atmosphere. Magic keeps normal gravity active on the surface of a shard, but there is none in the air between shards. Magic drives the plot, too, of course.

I assume the “Dave Duncan novel” is actually his “Dodec” duology: Children of Chaos and Mother of Lies, the setting for which is a dodecahedron-shaped world. It’s not his best work, but still decent, and the shape of the world is important to the plot. (Getting from one face to another is difficult because the edges are very high mountain ranges.)

I should note that at the start of the first book Duncan implies that he will explain the world shape, but the note at the end of the second book doesn’t really do this – it suggests that the inhabitants are misunderstanding the physical reality, but it’s not clear to me how as the physical reality shown seems to conform to what would actually exist on such a world, if of course we ignore the fact it couldn’t exist in the first place.

“Under the Pendulum Sun” is one of the most unique, original, intelligent novels I have ever read. Like its world, it sinks its tendrils into you and doesn’t let go. It’s not just “set” in fairy world — the whole thing *feels* like a bizarre, confusing, disturbing Wonderland, equally intriguing and horrifying. I read it over a year ago and still think of it constantly. From the historical, theological, and scientific research to the impeccably maintained tone, it’s just so well executed. I can’t wait till she writes something else!

Rachel Neumeir’s Tuyo series is set in a world where the primary locations we visit are the Winter Lands (cold, snowy, nomadic people) and south of that the Summer Lands (warm to hot, settled villages and cities). But it’s not a standard globe; the two territories are separated by a river, and the temperature changes abruptly in the middle of the river. There’s also Twilight Lands north of the Winter Lands (and very strange), and another territory south of the Summer Lands, even hotter, but we haven’t seen that yet.

See also “Circumpolar!” by Richard Lupoff. In this alt-hist novel, the Earth is a flattened torus, with all of the continents on one side, with an impenetrable ice wall surrounding the rim, with a polar “tunnel” running through to the other side, which has a whole different set of continents and societies. Set in the 1920’s the novel concerns an air race between two teams, one consisting of Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh and Howard Hughes, versus Manfred and Lothan Von Richtofen, to be the first to reach the North Pole entrance to the polar tunnel and travel through to the “other side.”

Although I despise what Microsoft has done to my favorite game, I still have an old copy of Minecraft on an Xbox 360 that can’t even connect to my wifi anymore (so ha ha on you, Microsoft, I actually own what I paid for). Last night I created a world with a random seed that has all of its cold biomes (birch forests, taiga, etc.) tucked on the right and top edges of its map while warm biomes (dark oak forest, swamp, coral seas, etc.) take up the rest. This is unusual for older versions of Minecraft, which typically throw random assortments of biomes around like confetti.

There are three villages: two in the warm area, one in the cold. I am already imagining their different cultures and the ways they explain their funny little capsule universe. The Overworld (the main playing area) is a place in which magic wire crates produce endless streams of monsters, air pockets at the bottom of the sea may lead to caves that have flowers and grasses growing in them, and all mammals are parthenogenetic.

The fantasy comic Die takes place on an icosahedral world, although unlike the Dave Duncan books mentioned, the comic does not have gravity work as in our universe — you can just step from one face to another, the edges are not the equivalent of mountain ranges. (James, if you haven’t read Die I highly recommend it to you.)

Lawrence Watt-Evans’ Ethshar series takes place on a flat world surrounded by a sea of chaos, sounding quite similar to the description of Glorantha and very possibly inspired by it.

In the Silmarillion as published, Tolkien’s Middle-Earth started out flat, which is how two really tall lamps could provide light for the whole thing, and was made a globe after a few thousand years had passed. Although I’ve read that later on he changed his mind about that.

What no Larry Nivea Ring World.

Ringworld is generally classified as science fiction, not fantasy.

Philip José Farmer and his World of Tiers series. Even the “Earth” is not like our Earth. The entire universe that Earth inhabits barely extends past Pluto. And then there are the various worlds where the laws and functions are very, very different.

Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence qualifies.

Then there’s Graydon Saunders’ Commonweal series.

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Shadows of the Apt and Echoes of the Fall.

Martha Wells’ Books of the Raksura series. Also her Ile Rien books (Element of Fire, Death of the Necromancer and Fall of Ile Rien trilogy), plus City of Bone and Wheel of the Infinite.

Science fiction/fantasy is a hoary false dichotomy. Science fiction worlds are fantasy worlds, of a particular flavor.

@7 the 360 version of minecraft stopped receiving updates back in 2018, it’s now considered a legacy version. It was widely available on disc too, I know I paid less than 20 for my physical 360 version. Any updates can also be deleted off your storage device if you wanted to play that consoles release version.

Weis & Nick man’s Deathgate cycle has a very unique world, and is SF hiding in fantasy in a way similar to the Pern novels.

Since you mentioned a TTRPG-world there should be a honorable mention of Planescape. It is technically many worlds, but the main setting, Sigil, could serve as an example. Sigil is a city positioned on the inside of a ring, atop a infinite pillar, at the absolute center of the multiverses many, infinite worlds. It is called The City of Doors because of its many portals, that may appear at almost any spot and time, and take you either to a demon infested hellscape with no chance of escape, or just two blocks down the street.

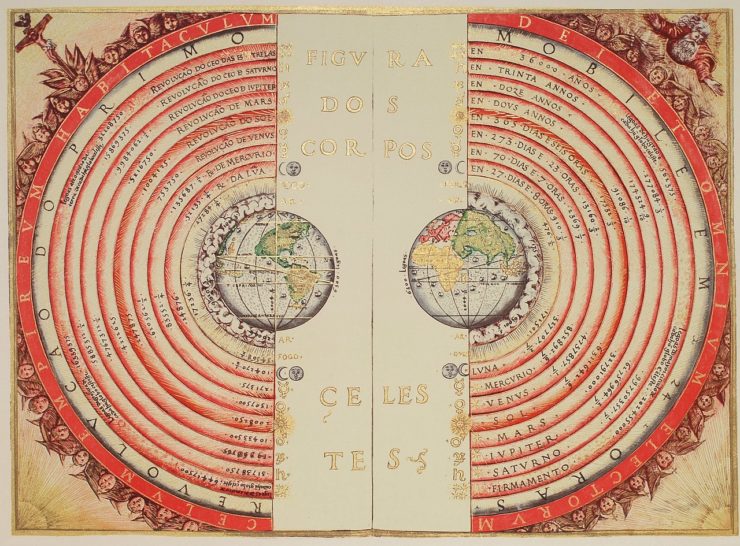

Celestial Matters by Richard Garfinkle (published in the 1990s) is a hard science fiction novel set in a version of our world in which Ptolemy and Aristotle were correct about the nature of the universe. The plot follows a military expedition to the sun (in a ship carved out of the moon), in order to bring back a cupful of solar matter as a superweapon.

I call it hard science fiction because the implications of the physics and astronomy are very rigorously worked out and adhered to, at least as far as I recall.

@14: I know; I have the latest X360 version (Part 1 of the Aquatic Update). I was playing Java Edition, but then they told me I had to get a Microsoft login to keep playing. And that they were going to put me on a monthly subscription because God forbid Microsoft let anybody actually own instead of renting. And so, having extensive experience with Microsoft tech support (sic) and the periodic upheaval of the Microsoft Experience (TM), I canceled my Minecraft membership.

Plugging in that old X360 and discovering that I can still play Minecraft while completely offline was a joyous surprise. Learning later that you now cannot opt out of having your usage and platform tracked if you want to play Java or Bedrock Editions, as part of the new Microsoft Experience–that just chipped away at my nostalgia for some of the features of Java Edition that the X360 doesn’t have. Learning that single-biome world generation is now broken by design extinguished my regrets entirely.

Speaking of which: If you can get your hands on an older Java Edition version–1.17 or earlier–with functioning single-biome world generation, it produces some intriguingly alien planets. I will elaborate for non-players.

The stone beach biome mimics the shore near Kilauea, with tiny green patches among frowning cliffs and rivers of lava. The world of Stone Beach (again, in 1.17 or earlier) looks like a meteor hit it dead on three years ago and it’s still bleeding fire. Harsh, yet beautiful. Every flower you find is precious.

The river biome produces long narrow bodies of water that don’t flow, but do look sort of river-ish, or maybe fjord-y. The world of River is an endless shallow lake with an earthen bed and schools of fish darting about; tiny flat islands poke up here and there. The tallest shapes on any horizon are the broken obsidian rings of ruined portals that, if you can repair and activate them, will take you to a fiery dimension called the Nether.

The desert biome is, of course, a desert: and unlike the two I already listed, it’s pre-populated with villages of charmingly foolish locals. The world of Desert is speckled with villages as far as the eye can see, but also gashed by deep ravines that expose long-forgotten ruins. Closer to the surface it’s riddled with sandy-roofed tunnels as if a bunch of drunken sandworms had run amuck. Knock down a tiny part of a tunnel roof and the rest of it will cave in; sometimes this collapse runs clear out of your field of vision–or into a village.

I never tire of Roger Zelazny’s “Jack of Shadows”— in an unturning world whose daylit side is like civilized earth, but whose night side operates strictly on magic.

Not a novel, but Ted Chiang’s ‘Tower of Babylon’ in his collection “Stories of Your Life” qualifies. While meant to read as if it was based in the Middle East, the ending clearly places it on a planet not based on Earth.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Sergei Prokofiev’s classic duo as modern art is awesome even today; like concrete, it is only getting stronger everyday.

Perhaps ‘Mune’ qualifies?

A world in which both sun and moon are flown across the sky, like giant kites on tethers. Said tethers attached to huge fantastical beasts which are guided across the surface of the land by beings chosen for the task.

@5: That’s Rachel Neumeier, not Rachel Neumeir.

As is well known but also explicated in “Trapped in the Sea of Stars”, the world of Newhon is the inside of a vast bubble, rising through the sea of eternity.

I do like the Flat Earth stories. Death is in them, like a lion in the desert.

Lifelode by Jo Walton. I don’t know what the shape of the world is, but to the east, there’s so little consciousness that people are automatons and to the west, there’s so much magic that identity is very unstable. The story is set in between, but a little toward the magic side.

The Soul Rider series by Jack Chalker are phenomenal. Fantasy by way of Science Fiction.

Without getting into whether this is SF or fantasy, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin Abbott Abbott is surely one of the strangest worlds in a novel, being entirely two-dimensional.

Some readers find Abbott’s character a bit flat.

@26 – You should try Greg Egan’s Dichronauts – a world with two spatial dimensions and two time-like dimensions. It’s Egan, so of course it’s rigorously worked out, but it still takes effort on the part of the reader.

The german fantasy TTRPG „Das schwarze Auge“ (The Dark Eye) features a subsetting called Tharun.

Tharun is a hollow world setting with a central sun which changes colour during the day and is black for the ten hours of the night. This alone changes some familiar characteristics of light.

First: shadows do not become shorter or longer during the day, as the sun is always vertically above.

Second: as the colour changes from black, violet, blue, red, orange and yellow to white and then back again to black, the perception of colour changes with it. As long as the sun is red, red objects seem to be black.

Small setting-features change a lot, if you look at their impact closely.

Walter Jon Williams’ Metropolitan features a very odd fantasy world – so odd that it’s often thought to be science fiction.

Jay Lake’s clockwork world stories, starting with Mainspring

While it also includes (multiple versions of) Earth, I thought D.J. MacHale’s Pendragon series did a really great job creating multiple worlds that feel nothing like Earth or the reality we live in.

James Davis Nicoll ICWYDT

Oh, yes, I thought Metropolitan was refreshingly different from our world.

Riverworld – Philip José Farmer. Classed as SF, i would put it in the same bucket as Missile Gap.

Broken Earth series – N. K. Jemisin

All the Hollow Earth books by various authors.

The multiple worlds in Chronicles of Amber by Roger Zelazny, is one of the best fantasy renderings of the multiverse and provides a whole range of worlds between Amber and the Courts of Chaos

@6: or, “Lifebuoy Earth”. :-) I take it that the “tunnel” is just the hole in the middle… for the record. ;-)

@28, Some readers find Abbott’s character a bit flat.

GROAN!!!!!

Can we include Arbre, from Anathem, here? btw reading it for the first time and I am so blown away, maybe the best thing I ever read

I thought of Roshar, and then Shadesmar, in the Stormlight Archive books. Roshar is a sphere like Earth, but it has one supercontinent spanning its southern hemisphere, seasons change rapidly and randomly in its temperate regions, and hurricanes sweep across the entire planet east-to-west with such frequency than most of the continent has no soil and most of the native plants and animals have shells. Shadesmar is an inverse mirror of Roshar and other worlds in the Cosmere; in its Roshar region, Roshar’s waterways are obsidian land, Roshar’s land is an “ocean” of glass beads, the sun never moves, the inhabitants are extremely un-Earthly, and that’s just the beginning of the weirdness.

As Cosmere worlds go, Taldain might be even weirder than Roshar in a way. It’s tidally locked, so that one half of it is constantly facing the sun and the other half is in eternal night. But its ecology and human cultures are well-adapted to this. Not so for the planet Aeon in The Never Tilting World by Rin Chupeco, where a recent cataclysm stopped the planet’s rotation and the side in endless night is being covered with ice and frigid water while the hot, rainless day side withers and burns.

“Then there’s Graydon Saunders’ Commonweal series.”

As far as I can tell, that world is very likely to be a magical version of Earth. Quite possibly actual Earth, at least 250,000 years in the future and subjected to lots of horrible magic, which seems to have been invented at some point, by a misanthrope.

Jack of Shadows: unusual world, but science fantasy, a tidally locked planet.

Twelve Kingdoms: a fantasy world, occasionally connected to Earth, consisting of 12 kingdoms arranged in a flat and symmetrical pattern. Apparently some god liked Imperial China so much he decided to make several copies of it, with a bunch of real magic thrown in. Gems grow in mines, babies grow on trees.

I wonder how Tolkein’s Middle-Earth would be considered here? Even though it’s our Earth, in conceit, the backstory involves the very shape of the world being changed by God.

Inverted World by Christopher Priest.

Would the world of the River in The Awakeners by Sheri S. Tepper count? It’s billed as science fiction, but it’s got zombies, shapechangers, magical herbs, and other fantastic trappings. Also, the people use familiar words, such as “river,” “bird,” and “fish,” but the further you read into the story, the more you understand that none of these words means what they do on Earth. The River appears to actually be a sea that girdles the planet and has a single near-shore current that goes all the way around. The birds talk and have plans of their own. And the fish are. Not fish.

Obligatory mention of M.A.R. Barker’s Tekumel.

http://www.tekumel.com

I think Steven Brust’s Dragaera, the setting for the Khaavren Romances, the Vlad Taltos novels, and Brokedown Palace, qualifies. They read as fantasy, even if some of the underpinnings, such as the origin and even presence of humans and the human-derived Dragaerans on the planet, may have a (semi-)science-fictional basis. There are greater and lesser seas of amorphia, an actual physical entrance to the underworld, and a physical representation of the Cycle that is tied to the real Cycle. Also other dimensions, one of which is inhabited by the enigmatic Jenoine, who created the situation on Dragaera through their magic (or science) and seek to return.

Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea for the most part is not remarkable as a world except for the fact that it’s composed entirely of islands, the largest of which may be about the size of New Guinea or Madagascar (if that large). If nothing else, that affects the cultures of the world, all of which are much more oriented toward the sea than our own, and that’s even before you factor in magic. (No horse nomads here!) There is also an “edge” of the world, at which there’s a wall that separates the lands of the living and the dead.

Is Delany’s Neveryona different enough to count?

@49 Yes and no, I’d suppose. The conceit of the story being derived from an ancient manuscript (the Culhar’ Fragment/Missolonghi Codex) gives it the feel of being an undefined part of our own prehistory or earliest written history.

The World of Exalted definitely qualifies, an island of reality with chaos in all four cardinal directions.

The fairyland in Jack Vance’s Lynonesse books is very un-earthlike. Likewise the fairyland in “Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell.” Both have physics that aren’t like our universe not to mention time. Vance’s Dying Earth stories often feature trips to other dimensions where things are just plain weird.

Uhmmm . . . what was that crack about Canadians? Yes, yes, I know, it was a joke. But I dunno, man.

Nine Princes in Amber. I mean, it is set partly on actual Earth, so that part isn’t so different. But clearly many of the Shadows you can get to are not working by remotely similar rules; for instance, that time Corwin was passing through some distant shadow, day broke, and he realized the “sun” was in fact a golden crown with a sword sticking up through it. And the Courts of Chaos is clearly not remotely earth-like, having a sky that is half black and half swirls of pastel colour, which rotates over the course of a “day” so that the black and pastel parts swap position. Plus a lot of other weird stuff. And the very nature of Amber, the shadows, and the Courts of Chaos represents a very not-just-earth cosmology.

I second Earthsea. As I recall, Ged sails so far that the water in the ocean becomes solid.

Also glad to see Tales from the Flat Earth in the list. That was the first that came to mind for me.

And of course Ringworld, though that’s science fiction.

The broken world of The Mirror Visitor series was the first that came to my mind, perhaps because I read it (again) just a few months ago and thoroughly enjoyed it.

The OP uses the word comprise in two opposite senses, sigh.

I realize many of his novels are considered difficult to classify, but I think China Miéville’s Railsea might belong among this list. Yeah, it’s weird fiction. It lacks any traditional fantasy elements, but it’s equally difficult to class his menagerie as scientifically rational. I love that he managed to set a whaling/pirate novel aboard locomotives operating on rails cross-crossing a sea of rocks and sand.

The “Land and Overland” series by Bob Shaw: The Ragged Astronauts; The Wooden Spaceships; and The Fugitive Worlds. Set in a universe where pi=3, the gravitational constant is different, and two planets can exist close enough to one another that crossing the gap by hot-air balloon is possible.

I submit for your consideration the worlds of The Eternal Sky books, by Elizabeth Bear, where the sky and the Sun change depending on which religion rules the land you’re standing on.

World Tree, by Bard Bloom and Victoria Borah Bloom. https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/TabletopGame/WorldTreeRPG

Role-playing game set on a tree thousands of miles tall, with branches fifty miles wide, and hundreds of thousands of miles long. The sun is an oil lamp that circled the universe.

There is a canonical novel _A Marriage of Insects_ and a semi-canonical series _Sythyry’s Journals_ based on a long running LiveJournal by (mostly) Bard.

@56 (Tamfang): I am beginning to think “comprise” is yet another lost cause, alas.

The world in Unicorn Jelly is incredible and weird. I’d mostly read the comic for that over the story. It’s a wrapping universe where millions of triangular planes hang equidistant from all neighbouring triangles. Each triangle is a world with land and ocean, and if it breaks, it will fall, and potentially break other worlds. The weird weather where air can harden in triangular patterns and suffocate people if it happens indoors is fascinating, too.

While it is true that Discworld bears very little physical resemblance to our world, it really isn’t all that un-Earthlike–the entire point of Discworld is to be Earthlike, particularly at the level the humanoids operate. Discworld is simply a place where things are less as they are and more as we imagine them to be (which is a paraphrase from the series, and no, I don’t remember which book, or it would have been an exact quote). Still excellent and worth reading, though.

I would nominate Anne Bishop’s Ephemera as a place that is truly un-Earthlike–where emotion shapes the landscape and the world is so fragmented that going between communities you aren’t guaranteed to be able to get back to where you started.

I have to make mention of C.S. Lewis’ Perelandra – a fantasy Venus with a sweet water ocean and floating “islands”. I’d love to taste the fruit that grows there.

Driftwood by Marie Brennan. The setting is definitely not Earth, more like a mosaic of worlds, but not exactly a world itself.

Paul Di Filippo’s “Linear City”.

I think the biggest islands in Earthsea are big enough that you could have horse culture on them, like England or Japan (Honshu). I don’t recall whether they actually have horses at all. I don’t think you can sail “to the edge”; the wall of the dead is something you need magic to reach.

@67 Large islands can certainly support a culture that uses horses, as you point out. According to most extant theories, the domestication of the horse took place in central Asia, in the rather immense plains/steppe grasslands area in which they probably evolved to their modern form, so any horse culture existing in Britain or Japan should be seen in the context of having been imported from the mainland by migrants already using horses. As you say, we’re not sure they even have horses at all in Earthsea; I don’t recall any mention of them.

@68 – I don’t remember any large terrestrial mammals at all in Earthsea, except humans and goats. Oh, and cattle. And the goats and cattle must have come with the humans when they colonized the Archipelago, there’s no mention of them having any wild relatives.

Island biogeography theory would apply here – the Archipelago is obviously a long ways away from any continent that it might share its world with, and there would have been a pretty strict filtering of possible animal species colonizing it from that continental source (assuming that there was one). Island biological diversity varies according to the size of the island and its distance from the mainland – the further away and smaller it is, the lower the diversity. That applies particularly to large mammals.

Of course, when we consider that Segoy raised the islands from the sea, and that human beings are apparently related to dragons, all of this becomes pretty moot.

May I suggest the True Game series by Sherri S. Tepper? Star-shaped creatures that roll along ancient roads. Ancient Gods in the form of a rodent, an eagle, and a forest. Talents to teleport, shapeshift, start and extinguish fires, find people, “Wizards” aka “Wise-art”

Yes, it is dressed up as Science Fiction, but I’d call it fantasy, and Lom (the world) bears almost no resemblance to Earth.

Is the Dave Duncan novel West of January? That was a weird one.

@71 West of January is set on a planet which has an ordinary shape, but which is almost tidally locked – the day is slightly shorter than the year. This has drastic consequences.